Secondary care

Antimicrobial stewardship in hospitals aim to optimise the use of antibiotics. This includes: making sure that antibiotics are only given to patients who really need them, choosing the most effective antibiotic, and prescribing the correct dose. This helps preserve the effectiveness of antibiotics are preserved for years to come.

- What we already know

- What questions did we ask?

- What did we find?

- Intervention development

- Resources and references

What we already know

Use of antimicrobials in UK hospitals

In the UK, hospitals are responsible for 20% of the total amount of antibiotics prescribed in humans. Compared with other healthcare environments, hospitals prescribe more broad-spectrum antibiotics, which are the drugs used for the most severe infections. Hospitals can also play an important role in transmitting infections to other settings such as the community, for example when an individual with an active infection is discharged to a care home.

There are signs that antibiotics are being overused in hospitals:

- UK hospitals have the second highest prescribing rate out of 22 European nations in number of doses per 1,000 resident (ECDC 2017)

- A survey of UK hospitals recently estimated that 17% days of therapy are avoidable (Public Health England 2015)

- A study in Oxford compared antibiotic use between general medical physicians and infection disease physicians, who are specialists in treating infections. The study found that infectious disease physicians used 30% less days of therapy (Fawcett et al. 2016)

Worryingly, prescribing of the ‘last resort’ antibiotics (reserved for infections resistant to multiple drugs or patients with a compromised immune system) has increased by 28% between 2011 and 2016 (Budd et al. 2019). These are mostly carbapenems and third-generation cephalosporins.

Data show strong variation in the type of antibiotics used across hospitals. Specialist (eg cardiothoracic, haematology/oncology, paediatric monospecialities) and teaching hospitals relied on large amounts of last-resort antibiotics.

Effectiveness of stewardship interventions

Stewardship interventions in inpatient care settings are safe and effective in both: improving clinical practice, and reducing antimicrobial resistance.

The most up-to-date and trusted systematic review of all evaluations published to date was released in 2017 in the Cochrane Library. Authors reviewed a total of 29 randomised controlled trials and 91 interrupted time series, and concluded that, overall, stewardship interventions are effective in relation to several outcomes:

- compliance with clinical guidelines: with intervention, 58% of patients were treated in accordance with antimicrobial guidelines, compared with 43% in a control group with no intervention

- duration of antimicrobial therapy was on average 2 days shorter with intervention

- length of hospital stay is an average 1 day shorter with intervention.

Authors also found no evidence that stewardship interventions increased mortality or other risks to patient safety.

A recent meta-analysis also provides some evidence that stewardship interventions reduce the prevalence of drug-resistant infections and transmission of drug-resistant bacteria. Baur et al. (2017).

Implementation of stewardship interventions globally

Globally, antimicrobial stewardship programmes are now established in most hospitals in high-income countries.

Howard et al. (2015) surveyed 660 hospitals across a total of 67 countries. Fifty-eight percent of hospitals had a dedicated antimicrobial stewardship committee in place, with the highest proportion in North America and Europe (66%) and a very low proportion in Africa (14%). This proportion ranged between 5 and 16% on other continents.

Worldwide, 62% of hospitals reported having local stewardship guidelines.

The survey revealed that antimicrobial stewardship programmes can be very demanding on health professionals’ time, skills and confidence, particularly when it comes to reviewing antibiotic prescriptions (Chung et al. 2013).

Implementation of stewardship interventions in the UK

Scobie et al. (2019) surveyed stewardship initiatives across 148 NHS acute trusts in England in 2017. They found that

- 85% restricted the use of some antibiotics, requiring a senior infection doctor or pharmacist to pre-authorise their prescription

- 93% had dedicated a dedicated antimicrobial stewardship team, including at least an antimicrobial pharmacist and a microbiology/infectious diseases doctor

- 99% had hospital prescribing guidelines for common infections

- 82% organised an expert review of prescriptions for specific antibiotics, with microbiology/infectious disease specialists or pharmacists giving feedback and advice to prescribers.

Half of hospitals (73/148) had a microbiologist conduct routine and regular ward rounds to review antibiotics at least once a week; 23% (34/148) did so every day (weekends included). The most commonly audited area was intensive care units (146/148), followed by medical wards (64%), surgical wards (60%) and haematology wards (58%).

Almost all hospitals were able to measure antimicrobial consumption, but only 31% (46/148) of surveyed hospitals regularly fed this information back to prescribers.

Antibiotic prescription reviews

Antibiotic prescription reviews or ‘prospective audits’ involve the review of antibiotic prescriptions on wards by infection specialists, usually either an infectious diseases physician, a clinical microbiologist, or a clinical pharmacist. They are frequently described as the most effective strategy to optimise prescribing (Chung et al. 2013).

Advantages of antibiotic prescription reviews are:

- they are more supportive and therefore better received by doctors than pre-authorisation of antibiotics.

- they usually take places at the bedside (rather than over the telephone, when infection specialists cannot fully assess the patient);

- they provides an opportunity for doctors to learn more about infections.

Disadvantages of antibiotic prescription reviews are:

- They are time-consuming

- They require up-to-date lists of patients taking antibiotics

- Their reach can be limited by person-power: the median number of occupied beds in an English acute trust is 500. Out of those, 175 are occupied by patients taking antibiotics at any time. The median number of infection specialist is just 5 working time equivalents, occupied with many other duties.

- Some areas of clinical practice are not supported by strong scientific evidence and guidelines. For instance , experts do not know for sure when and how antibiotics should be ‘de-escalated’; that is, how soon antibiotics can safely be stopped or changed for another drug with a narrower spectrum (Hughes et al. 2017, Tabah et al. 2020).

What questions did we ask?

Review of published evidence

Although systematic reviews of stewardship interventions are available (see above), there is wide variation in the effectiveness of similar interventions across different settings. If we want to know which interventions are most likely to be effective, we need to know why they work.

In other words, we need to understand what are the ‘active ingredients’ of effective stewardship interventions.

Behavioural science can be used to specify the ‘active ingredients’ of behavioural interventions, by coding them as behaviour change techniques (BCTs). To this end, health psychologists from PASS read through all 221 behavioural interventions reported in the systematic review by Davey et al. (2017). They coded for the presence of BCTs and then assessed how often effective interventions included specific types of BCTs. This provides evidence about the types of BCTs that should be included in future stewardship interventions.

Electronic health records

As of June 2019, over half of acute NHS Trusts operated an electronic prescribing and administration system, but these systems do not currently play a major role in stewardship programmes. We aimed to test whether and how electronic records of prescriptions, microbial samples, and patient investigations (blood counts, vital signs) could be used to identify where antimicrobial use could be optimised.

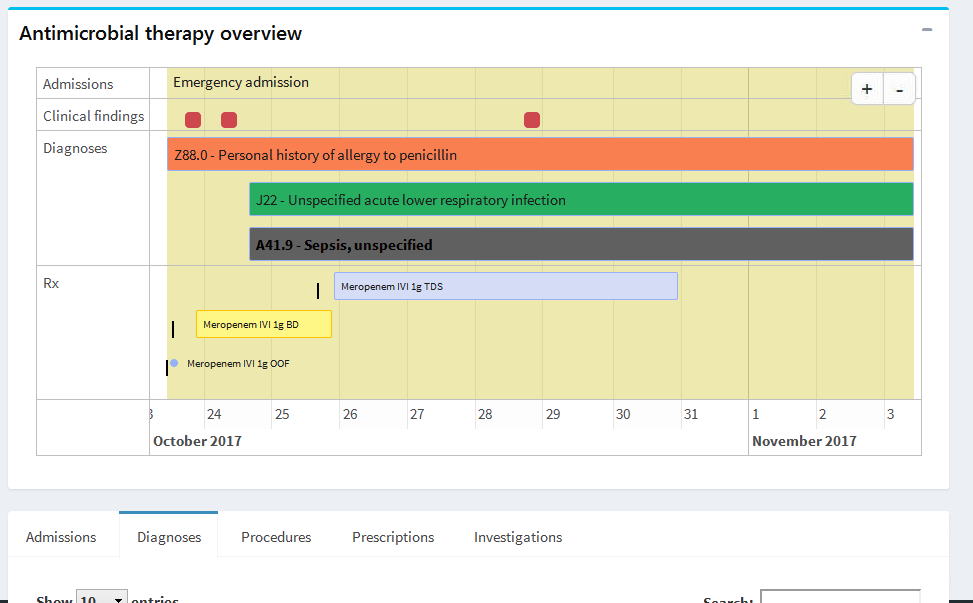

Our study partner, Queen Elizabeth Hospital Birmingham, provided the study team with anonymised patient records for adults who were admitted to hospital between 2008 and 2018. Researchers at University College London developed a range of software tools to visualise and analyse the data. The picture below shows a view from a prototype app used to compare compliance of antibiotic prescribing against the hospital’s stewardship guidelines.

Interviews of prescribers

The aim of the interviews was to understand who performs antibiotic reviews, as well as when and how decisions to switch from intravenous to oral therapy and to stop antibiotics are made as part of antibiotic stewardship. The interview questions were developed using a theoretical informed behaviour change framework to identify the likely enablers and barriers of conducting reviews of antibiotics and switching or stopping antibiotic prescriptions (Atkins et al. 2017). Interviews took place in an NHS Foundation Trust hospital in England within low and high prescribing wards. Interviews were conducted with consultants, registrars, junior doctors and pharmacists across 4 specialist wards.

Observations

A researcher conducted non-participant observation, and informal conversations with staff, in medical wards at an NHS Foundation Trust hospital in England. Four consultant teams with varying levels of antibiotic use were sampled based on information from hospital databases based on their record of prescribing. The researcher observed a total of four wards during a total of 123 hours.

The researcher recorded detailed handwritten field notes while at the research site, and audio recorded details from the field notes, reflections and interpretations. These audio recordings were then transcribed and analysed alongside pictures and policies/guidelines collected from the research site.

Data were analysed using a thematic analysis approach assisted by NVivo software to identify influences on antibiotic stewardship. Analysis was informed by a framework of six universal challenges to improving quality commonly faced by healthcare organisation (Bate et al. 2008).

Design workshops

We held one 2-hour workshop at a UK hospital where we had also completed interviews and observations. 14 staff from the acute medical unit (AMU) attended. Staff included pharmacists, consultants, registrars, nurses and advanced level practitioner nurses.

We asked staff about daily pressures and stresses that might be impacting stewardship goals generally, and discussed attitudes and barriers around de-escalating. We also explored the role of intravenous antibiotics. Participants undertook 3 hands-on activities within smaller clinical role groups, followed by whole-group discussions.

What did we find?

Review of published evidence

Interventions delivered in hospital inpatient settings employed 29 out of a total of 93 behaviour change techniques (BCTs), highlighting that many BCTs are not used at all.

The average number of BCTs in each intervention was 4.5, showing that interventions are designed as a complex combination of techniques.

The five most common BCTs were:

BCT 4.1 Instructions on behaviour

73% of interventions

Definition Advise or agree on how to preserve antibiotics (including skills training)

Example

- Revision of guidelines to recommend penicillins as first-line drugs and discouraged use of other antibiotic classes.

BCT 9.1 Credible source

66% of interventions

Definition Present verbal/visual communication from a credible source in favour of antibiotic stewardship. Credible sources can be:

- clinical evidence

- a recognised health body (eg WHO, NICE)

- a senior team member or designated champion with specialist knowledge or training

Example

- Feedback to prescribers by an antimicrobial pharmacist or an infectious disease physician

BCT 12.1 Restructuring physical environment

61% of interventions

Definition Change/advise to change the physical environment in order to facilitate antibiotic stewardship (may include BCT 12.5 'Adding objects to environment').

Examples

- Redesigning microbiology test order forms and reports to increase microbial sampling and provide faster results

- Redesigning e-prescribing systems to stop all prescriptions at 48 hours, forcing clinicians to review/extend antibiotics in the first two days.

BCT 12.5 Adding objects to environment

38% of interventions

Definition Add objects to the environment in order to facilitate antibiotic stewardship

Examples

- Adding a new antibiotic to a formulary

- Introducing new point of care diagnostics machines

BCT 12.2 Restructuring social environment

37% of interventions

Definition Change, or advise to change the social environment in order to facilitate facilitate antibiotic stewardship behavior or create barriers to poor use of antibiotics

Example

- Microbiologists provide a telephone support service

However, when analysing the effect of individual BCTs on intervention effectiveness, the statistical analysis only detected one interaction: interventions with BCT (1.2) Problem solving were more effective than other interventions. Problem solving consists in analysing, or prompting the person to analyse, factors influencing their prescribing and bringing forward strategies to overcome barriers to improve prescribing.

Electronic health records

Using hospitals’ routine electronic prescribing and laboratory records, we were able to measure many characteristics of antimicrobial stewardship (Dutey-Magni et al. 2021):

- length of antimicrobial therapy by type of infection

- congruence of prescribing with prescribing guidelines: for instance, we found that only 22% of low-severity community-acquired pneumonia were initiated using the recommended drug choice.

- de-escalation from broad-spectrum antibiotics: looking at meropenem, we found that 30% of treatment initiated with meropenem was stopped after a mean of 3 days, and 46% was switched to another class of antibiotics.

- microbial cultures are taken prior to starting therapy in only 22% of therapy episodes

Such measures can be derived at the level of clinical teams, wards, and specialties in any hospital equipped with electronic prescribing and laboratory system. In 2020, over 50% of hospitals in England had such system. The Department of Health aims to reach 100% by 2025.

Enabling all hospitals to report such metrics on a regular basis would strengthen local Antimicrobial Stewardship teams and improve the use of antibiotics in secondary care.

The UK’s National Action Plan 2019–24 aims to be able to report on the percentage of prescriptions supported by a diagnostic test or decision support tool by 2024.

Interviews

Multiple behaviours performed by different clinical roles contribute to the use of antibiotics. Starting antibiotics and later decisions taken at review were pivotal for antibiotic selection and delivery (IV or oral) and for switching or stopping antibiotic therapy. Initial prescribing was often empirical and precautionary because of diagnostic uncertainty and a lack of information from test results. Switching or stopping antibiotics was considered more straightforward because diagnostic and test results were documented, and there were opportunities to discuss appropriate antibiotic use with other clinicians. Variation in antibiotic therapy was reported across the sampled wards and units (Clinical dependency unit, and Stroke and Diabetes wards).

Several key themes were identified within the behavioural domains that could positively or negatively influence the appropriate use of antibiotics. These tended to largely influence at the review of antibiotic therapy and not at initiation because this was when the 10 participating clinicians became involved in the patients’ care.

Key enablers were system level feedback on prescribing practice, i.e. dashboard; availability of point of care tools e.g. flu machine, guideline Apps; timely dissemination of guidelines; having sufficient time to spend with patients and supporting advice from senior clinicians, microbiologists and pharmacists. Key barriers were concerns about something being missed, waiting time for results, perceived risks of not continuing with antibiotics, and lack of focus on antibiotic stewardship.

Themes acting as both a barrier or an enabler of prescribing decisions of starting antibiotics included varying confidence in diagnosing infections and of when to use or not use antibiotics and varying views about having the skills and competence to switch or to stop antibiotics. Other influences were perceptions about the benefits or disadvantages using antibiotics, level of pressure to prescribe (from other clinicians), regular or infrequent referring to guidelines, agreement or disagreement with the original diagnosis and ability to cope with direct requests from patients and relatives for antibiotics.

All clinicians placed great importance on reducing antibiotic resistance, however engaging in antibiotic stewardship was considered to be complex because of the many interacting individual and system-level components.

Observations

Roles and responsibilities Staff worked in teams on wards and across the hospital as a whole and responsibilities for antibiotics were distributed across teams and systems.

In theory each member of staff has an individual responsibility toward Infection Prevention and Control (IPC) and Antimicrobial Stewardship (AMS), but in practice some were less aware of it than others: IPC was seen as sitting primarily within the domain of nursing staff; AMS with clinicians.

Coordination of decisions along the patient pathway In secondary care, patients arrived in the ED acutely unwell and clinicians needed to act fast to stabilise and prevent deterioration; they erred towards prescribing antibiotics. Staff felt under pressure to ensure that no infection was missed.

High demand on services also meant delays in access to and results from diagnostic testing. Wards were often understaffed, and multiple handovers could result in diffusion of responsibility for reviewing and stopping antibiotics.

Systems and tools for stewardship Tools such as guidelines and computer software could assist with prescriber decision-making. Electronic prescribing software enabled prescribing restrictions to be enforced and individuals who prescribed problematically to be identified and ‘reprimanded’, but monitoring people’s prescribing could produce unintended behaviours including workarounds.

Experts in prescribing and stewardship Both pharmacy and microbiology played a central role in antibiotic prescribing and stewardship but their involvement varied across the wards.

Design workshop

For the AMU team, we found that:

- antibiotics often needed to be started where infection assessments were inconclusive

- there was a sense of safety in continuing treatment

- treating potential sepsis was a more immediate concern than de-escalation

- antibiotics were often commenced intravenously

- not all prophylaxis antibiotics (such as before an operation) may be necessary.

Staff suggested that the following would help them to better support good stewardship:

- better information about the patient’s history and current problem

- improved opportunities for intensive or more regular one-to-one monitoring and care

- choosing the most appropriate test, and getting test results swiftly

- better access to local resistance information, guideline updates, key stewardship training and ward prescribing performance

- good team work and clearer delegation of tasks and responsibilities for stewardship

- opportunity to contribute to treatment decisions, regardless of clinical role.

Intervention development

We are using what we have learnt and to develop interventions that will address antibiotic resistance in healthcare. This involves:

- reviewing barriers and facilitators of stewardship

- identifying mechanisms of change and behaviour change techniques

- collaborating with practitioners to decide how best to deliver behaviour change techniques in terms of feasibility and acceptability.

PASS Interventions

PASS Interventions Presentation

(PDF, 2.5Mb)

Resources and references

Guidelines & toolkits

Public Health England (2015). Start Smart--Then Focus. Antimicrobial Stewardship Toolkit for English Hospitals. Available online

Gyssens, I. C., Van Den Broek, P. J., Kullberg, B.-J., Hekster, Y. A., & Van Der Meer, J. W. M. (1992). Optimizing antimicrobial therapy. A method for antimicrobial drug use evaluation. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 30(5), 724–727. DOI: 10.1093/jac/30.5.724

National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (2015). Antimicrobial stewardship: systems and processes for effective antimicrobial medicine use. NICE guideline NG15. Available online

Stichting Werkgroep Antibioticabeleid (2016). SWAB Guidelines for Antimicrobial Stewardship. Available online

Surveys

Howard, P., Pulcini, C., Levy Hara, G., West, R. M., Gould, I. M., Harbarth, S., & Nathwani, D. (2015). An international cross-sectional survey of antimicrobial stewardship programmes in hospitals. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 70(4), 1245–1255. DOI: 10.1093/jac/dku497

Van Gastel, E., Costers, M., Peetermans, W. E. E., & Struelens, M. J. J. (2010). Nationwide implementation of antibiotic management teams in Belgian hospitals: A self-reporting survey. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 65(3), 576–580. DOI: 10.1093/jac/dkp470

Chung, G. W. W., Wu, J. E. E., Yeo, C. L. L., Chan, D., & Hsu, L. Y. Y. (2013). Antimicrobial stewardship. Virulence, 4(2), 151–157. DOI: 10.4161/viru.21626

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (2017). Antimicrobial consumption -- Annual Epidemiological Report for 2017. Stockholm: ECDC. Available online.

Scobie, A., Budd, E. L., Harris, R. J., Hopkins, S., & Shetty, N. (2019). Antimicrobial stewardship: an evaluation of structure and process and their association with antimicrobial prescribing in NHS hospitals in England. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 74(4), 1143–1152. DOI: 10.1093/jac/dky538

Reviews

Baur, D., Gladstone, B. P., Burkert, F., Carrara, E., Foschi, F., Döbele, S., & Tacconelli, E. (2017). Effect of antibiotic stewardship on the incidence of infection and colonisation with antibiotic-resistant bacteria and Clostridium difficile infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 17(9), 990–1001. DOI: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30325-0

Davey, P., Sneddon, J., & Nathwani, D. (2010). Overview of strategies for overcoming the challenge of antimicrobial resistance. Expert Review of Clinical Pharmacology, 3(5), 667–686. DOI: 10.1586/ecp.10.46

Davey, P., Peden, C., Charani, E., Marwick, C., & Michie, S. (2015). Time for action - Improving the design and reporting of behaviour change interventions for antimicrobial stewardship in hospitals: Early findings from a systematic review. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents, 45(3), 203–212. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2014.11.014

Davey, P., Marwick, C. A., Scott, C. L., Charani, E., McNeil, K., Brown, E., … Michie, S. (2017). Interventions to improve antibiotic prescribing practices for hospital inpatients. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (2). DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003543.pub4

Morris, A. M. (2014). Antimicrobial Stewardship Programs: Appropriate Measures and Metrics to Study their Impact. Current Treatment Options in Infectious Diseases, 6(2), 101–112. DOI: 10.1007/s40506-014-0015-3

Schuts, E. C., Hulscher, M. E. J. L., Mouton, J. W., Verduin, C. M., Stuart, J. W. T. C., Overdiek, H. W. P. M., … Prins, J. M. (2016). Current evidence on hospital antimicrobial stewardship objectives: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 16(7), 847–856. DOI: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)00065-7

Other research

Atkins, L., Francis, J., Islam, R., ..., Michie, S. (2017). 'A guide to using the Theoretical Domains Framework of behaviour change to investigate implementation problems', Implementation Science, 12, 77. DOI: 10.1186/s13012-017-0605-9

Bate, P., Mendel, P., & Robert, G. (2008). Organizing for Quality: The Improvement Journeys of Leading Hospitals in Europe and the United States. Research report. London: Nuffield Trust. Available online

Broom, J., Broom, A., Plage, S., Adams, K., & Post, J. J. (2016). Barriers to uptake of antimicrobial advice in a UK hospital: A qualitative study. Journal of Hospital Infection, 93(4), 418–422. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhin.2016.03.011

Budd, E., Cramp, E., Sharland, M., Hand, K., Howard, P., Wilson, P., …, Hopkins, S. (2019 ). Adaptation of the WHO Essential Medicines List for national antibiotic stewardship policy in England: being AWaRe. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 74(11), 3384–3389. 10.1093/jac/dkz321

Chung, G. W. W., Wu, J. E. E., Yeo, C. L. L., Chan, D., & Hsu, L. Y. Y. (2013). Antimicrobial stewardship: A review of prospective audit and feedback systems and an objective evaluation of outcomes. Virulence, 4(2), 151–157. DOI: 10.4161/viru.21626

Dutey-Magni, P. F., Gill, M. J., McNulty, D., Sohal, G., Hayward, A., & Shallcross, L. (2021). Feasibility study of hospital antimicrobial stewardship analytics using electronic health records. JAC-Antimicrobial Resistance, 3(1). DOI: 10.1093/jacamr/dlab018

Fawcett, N. J., Jones, N., Quan, T. P., Mistry, V., Crook, D., Peto, T., & Walker, A. S. (2016). Antibiotic use and clinical outcomes in the acute setting under management by an infectious diseases acute physician versus other clinical teams: a cohort study. BMJ Open, 6(8), e010969. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010969

Hughes, J., Huo, X., Falk, L., Hurford, A., Lan, K., Coburn, B., ..., Wu, J. (2017). Benefits and unintended consequences of antimicrobial de-escalation: Implications for stewardship programs. PLOS ONE, 12(2), e0171218. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171218

Tabah, A., Bassetti, M., Kollef, M. H., Zahar, J.-R., Paiva, J.-A., Timsit, J.-F., ..., Garnacho-Montero, J. (2020). Antimicrobial de-escalation in critically ill patients: A position statement from a task force of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM) and European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) Critically Ill Patient. Intensive Care Medicine, 46(2), 245–265. DOI: 10.1007/s00134-019-05866-w

Textbooks

LaPlante, K. L., Cunha, C. B., Morrill, H. J., Rice, L. B., & Mylonakis, E. (Eds.). (2017). Antimicrobial stewardship: principles and practice. Wallingford: CABI. DOI: 10.1079/9781780644394.0000

Laundy, M., Gilchrist, M., & Whitney, L. (Eds.). (2016). Antimicrobial Stewardship (Vol. 1). Oxford University Press. DOI: 10.1093/med/9780198758792.001.0001